|

Spain and Wine

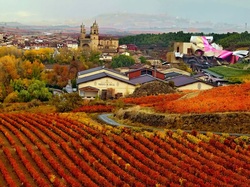

Although Spain has thousands of wines, we have made a good selection of some of the best Spanish wines, with Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), from different regions of Spain, as Rioja, Ribera del Duero, Toro, Bierzo, Priorat, Jumilla, Campo de Borja and Ribeira Sacra for Red wines; Rueda, Rías Baixas and Ribeiro for White ones; Sherry and Montilla-Moriles for Fortified wines and Cava for Sparkling wines. We also have some of the best and famous Brandies. Spain is one of the Top Ten wine producer countries of the world and we would like to let you taste some of its wines, with a great variety of grapes but also very different between the Spanish regions. All wines are in 0,75 litre bottle, although if you need a special size (as 1,5 litre Magnum, 0,5 litre or 0,375 litre), or if your favourite Spanish wine is not in our list, please ask for it and we'll look for it and send it to you. |

Spain is an ancient wine-producing country and produces nearly as much wine as the number-one and number-two wine producers in the world: Italy and France. Spanish wine is at least 3,000 years old; vineyards in today’s Sherry region were planted by the Phoenicians around 1100 BC. Wines from vines grown along the sunny Mediterranean coast and the cooler Atlantic coast were traded and consumed by the Romans. But the arrival of the tee-totaling Islamic Moors in 711 AD put an end to Spanish wine commerce until the Moors’ defeat in 1492. With the Iberian Peninsula freed from Islamic rule, wine returned as part of daily life, no more important, and no less, than the daily bread.

Only in the modern era of commerce has food and drink become something more than local. Though wines as far–flung as Tokaji, Constantia, and Commandaria once commanded the world's attention, by the mid nineteenth century the French owned the spotlight. Sherry, Falstaff's beloved drink, remained a stock character on the stage, but the rest of Spain's vinous players stayed largely in the wings. It was only the sudden arrival of the destructive phylloxera pest among the vineyards of Bordeaux, France's principal lead, that allowed Rioja its brief turn on that stage.

Wealthy producers such as the Marqués de Riscal and Marqués de Murrieta had the wherewithal to produce Rioja wines that garnered attention, even if limited to Spain. Once phylloxera was quashed, Bordeaux returned to health and prominence, and like all good understudies, Rioja returned to the chorus. Bordeaux, however, had left behind a style of winemaking that still influences Spanish wine today. We will see below just how long aging in barrel was learned from nineteenth century Bordeaux winemakers and how their ideas linger.

Only in the modern era of commerce has food and drink become something more than local. Though wines as far–flung as Tokaji, Constantia, and Commandaria once commanded the world's attention, by the mid nineteenth century the French owned the spotlight. Sherry, Falstaff's beloved drink, remained a stock character on the stage, but the rest of Spain's vinous players stayed largely in the wings. It was only the sudden arrival of the destructive phylloxera pest among the vineyards of Bordeaux, France's principal lead, that allowed Rioja its brief turn on that stage.

Wealthy producers such as the Marqués de Riscal and Marqués de Murrieta had the wherewithal to produce Rioja wines that garnered attention, even if limited to Spain. Once phylloxera was quashed, Bordeaux returned to health and prominence, and like all good understudies, Rioja returned to the chorus. Bordeaux, however, had left behind a style of winemaking that still influences Spanish wine today. We will see below just how long aging in barrel was learned from nineteenth century Bordeaux winemakers and how their ideas linger.

The State of Spain and its wines

Spanish wine has kept pace, generating an explosion of new wines, wineries, brands, and regions that is unprecedented in vinous history. While wine has underpinned commerce and nutrition in Spain for thousands of years, what we are seeing today is something that no other country has ever experienced, a compressed revolution in which pedestrian, paint-by-numbers wine becomes great art. It's as if the last century of wine development in the most successful wine-producing countries has been achieved in only a few short years.

During the past decade and a half, the number of top-rung Spanish wine regions (Designations Of Origin or DOs) has grown by more than a third to a total of 69, and Spain has created a new set of laws, doubling the wine quality categories and introducing top wines from regions never known for quality wine or, more often, never even heard of at all.

During the past decade and a half, the number of top-rung Spanish wine regions (Designations Of Origin or DOs) has grown by more than a third to a total of 69, and Spain has created a new set of laws, doubling the wine quality categories and introducing top wines from regions never known for quality wine or, more often, never even heard of at all.

Spain’s Wine Revolution

The last few decades of Spanish wine have been as crazy a roller-coaster ride as any thrill seeker could hope to find. In the early 1980s, Rioja was the only region to garner international critical praise (much of it left-handed), Sherry was on a serious downhill slide, and Spanish white wine was invisible. Even Ribera del Duero was ignored, with pioneer Pesquera roundly ridiculed in the European press as having absurd pretensions of excellence. But by the late 1980s, the Europeans had changed their tune; Pesquera and especially its top bottling, Janus, were all the rage. Spanish white wine, dramatically improved, gained a foothold, led by Albariño.

Before long, wines from obscure or dismissed regions such as Priorat were on fire, with prices rising faster than tempers at a presidential debate. Places known only for cheap and cheerful wines (e.g., Jumilla) were suddenly garnering lofty scores from critics. And the Spanish bureaucrats played their part too, creating new DOs and an entirely new category of wine classifications: Vino de Pago. Representing a Spanish monopole (the French term for a vineyard with one owner, producing wine solely from that vineyard), the Vino de Pago concept also suggests something akin to a Grand Cru property. Even more interestingly, the first Vino de Pago were located near Madrid, among vineyards that never had been associated with high-quality wines.

Rioja never really lost its edge. While traditional Rioja wines were blended from its three subregions and multiple grapes and aged in used American oak barrels, new Rioja wines utilized single estates and vineyards, Tempranillo grapes (sometimes with a dollop of Graciano), and new French oak. Power and dark color became the hallmark of excellent Rioja instead of the mellow, earthy character that exemplified Riojan wines in the decades before.

For traditionalists, confusion reigns. But if the hidebound can simply lighten up a bit, they would see that modern Spanish wine is on a brilliant ride. All those new DOs represent a lot more than bureaucratic finagling; some of these additions describe new grapes and new regions, and many nurture the most exciting new wines the world has seen.

Before long, wines from obscure or dismissed regions such as Priorat were on fire, with prices rising faster than tempers at a presidential debate. Places known only for cheap and cheerful wines (e.g., Jumilla) were suddenly garnering lofty scores from critics. And the Spanish bureaucrats played their part too, creating new DOs and an entirely new category of wine classifications: Vino de Pago. Representing a Spanish monopole (the French term for a vineyard with one owner, producing wine solely from that vineyard), the Vino de Pago concept also suggests something akin to a Grand Cru property. Even more interestingly, the first Vino de Pago were located near Madrid, among vineyards that never had been associated with high-quality wines.

Rioja never really lost its edge. While traditional Rioja wines were blended from its three subregions and multiple grapes and aged in used American oak barrels, new Rioja wines utilized single estates and vineyards, Tempranillo grapes (sometimes with a dollop of Graciano), and new French oak. Power and dark color became the hallmark of excellent Rioja instead of the mellow, earthy character that exemplified Riojan wines in the decades before.

For traditionalists, confusion reigns. But if the hidebound can simply lighten up a bit, they would see that modern Spanish wine is on a brilliant ride. All those new DOs represent a lot more than bureaucratic finagling; some of these additions describe new grapes and new regions, and many nurture the most exciting new wines the world has seen.